Everyday conversation has a tick-tock rhythm, like this:

How about sushi for dinner?

Nah, how about Italian?

I'm thinking Mexican.

I can't eat that stuff, you know it gives me allergies.

What about that new Chinese place that opened last month?

Tick tock tick tock, right? But when somebody tells a story, the tick-tock rhythm stops for a while, because only one person has the floor to speak. A conversation with a story in it goes more like this:

What about that new Chinese place that opened last month?

You know, I went to that new Chinese place last week. I think it may even be better than our usual place. They had seven kinds of dumplings, and they gave me a whole pot of tea. The waiter wasn't rude, and the bathroom was clean. That's the most important thing, you know.

I know. How about we go there?

I'm still thinking Mexican.

Oh come on! You always say that.

Because of this change to the conversational rhythm, telling a story is both a privilege (because people are listening) and a risk (because people might not like what they hear). To reduce the risk (and enjoy the privilege) of storytelling, we learn from an early age to surround the sharing of stories with ritualized communications.

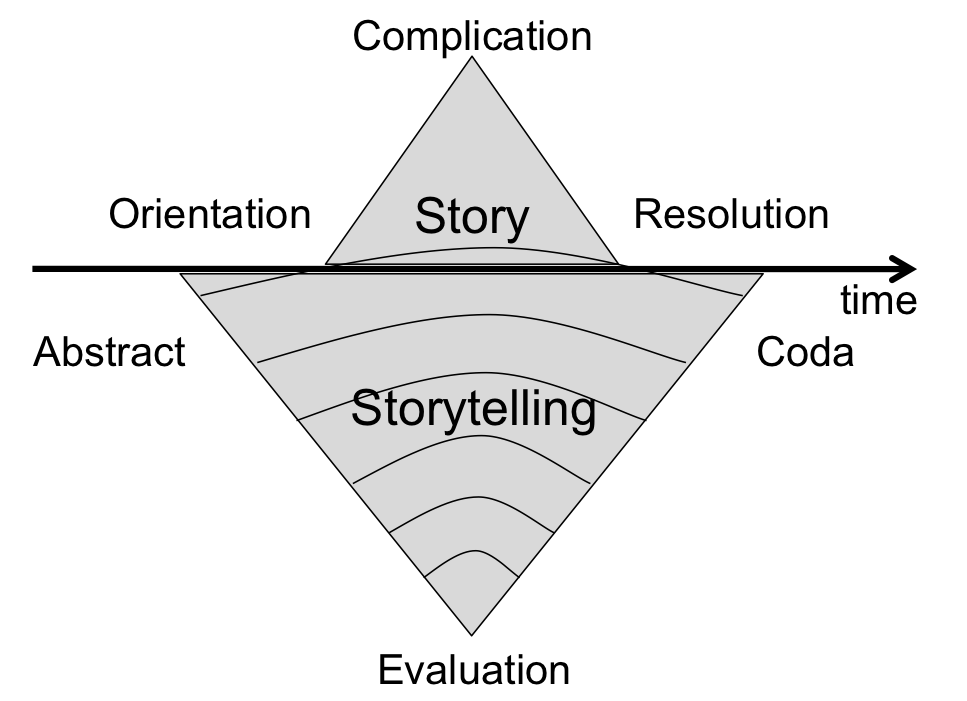

The shape of a conversational storyThe narrated events in any told story are the same as those we recognize from movie plots. In the orientation, the setting and characters are described. In the complication, the story's protagonists face challenges and respond to them. The resolution completes the story. Simple, right? But there is more to conversational storytelling than what you see above the surface. In a conversational story, three categories of narrative events negotiate permission to tell and willingness to listen. |

The abstract: How about a story?The storytelling ritual starts with an abstract, a negotiated offering to tell a story. People might say "One day..." or "My aunt Jessie used to..." and then pause to see if people are listening. If people stop talking and pay attention, the storyteller goes on. During story abstracts, people usually do some quick alteration of the story to fit the conversation. They might:

These alterations are carried out to introduce the story and to make it work for the current social context. During such adjustments, the audience may actively attempt to channel the proposed story into a presentation they prefer over what has been offered at the start. Perhaps they want the story to be more exciting than has been presented, or more on topic, or less revealing. Negotiations may encompass tone of voice, body language, and facial expression as well as words. Narratopia's connection cards become story abstracts when players fill in the blank spaces in them (thus fitting them to the conversation). The texts on the connection cards are based on some of the reasons people respond to stories with stories, such as:

|

The evaluation statement: This story is worth listening to.Once a group member's story abstract has been accepted, the person tells their story. During the telling of a conversational story, its teller usually peppers it with evaluation statements. These are "extra" comments that aren't necessary to move the plot of the story forward. Evaluation statements are direct lines of communication from storyteller to audience, and they all contain one message: this story is worth hearing. And it is still worth hearing, and it is still worth hearing. Say I am telling you a story about my dog being old and tired. When I get to the part where he was too old to walk up the driveway, I say, “I never saw a dog so exhausted in my life.” Why did I say that when simply saying “he was very tired” would have sufficed to recount the event? The real meaning of that sentence was, “This story stands out from my entire experience as significant, thus it will be significant for you too — so I recommend you keep listening.” When people make evaluation statements, they often:

Narratopia doesn't explicitly support evaluation statements because they take place within the telling of the story. Interrupting the conversation when a story is being told would not be helpful. However, as people listen to stories and look over the question cards in their hands, they connect questions to evaluation statements in order to choose appropriate questions to ask. |

The coda: I'm done, let's talk.The ending point of a conversational story, called its coda, is yet another piece of ritualistic negotiation. In a story’s coda, the storyteller closes the circle of narrated events and ends the narrative event, returning the time frame to the present and the control of the floor to the group. Usually during the coda people offer up additional proof that the story was worth listening to by:

Narratopia's question cards support story codas by giving people interesting questions to ask and answer. This helps the group negotiate the close of the story in a way that is satisifying to everyone. The texts on the question cards are based on typical audience responses during narrative events, including:

|

Why we do it

Why do we enclose our stories in these complex layers of ritualized negotiations? Why don’t we just tell them as they are?

I like to explain negotiation during storytelling using the metaphor of wrapping paper. When we bring someone a present and wrap it with special paper, the paper is a physical representation of a ritualized message. It says, "This gift is an offering from me to you. Out of consideration for my feelings, please do not destroy or discard the gift in front of me. At least pretend you like it and appreciate the gesture."

People often surround gift-giving with gestures that communicate a wrapper-like appeal: tentative, do-you-like-it smiles; open, extended hands or arms; "ta-da!" performances in sing-song voices; banners strung across doorways. All of these are social signals that set up a context of noncritical acceptance. We teach our children to recognize these signals and accept gifts graciously even (or especially) when they are unwanted.

Stories work in the same way, and at two levels. An outer layer of wrapping is made up of conversational rituals that surround storytelling and wrap stories in banner-like announcements of intent and preferred response. An inner layer is the story itself, which is a package we use to safely disclose feelings, beliefs, and opinions without making claims to truth that would be open to immediate dispute without it. Most well-brought-up people recognize the double-layered wrappings of a story and respond accordingly. Those who will not let others tell stories probably don’t get many wrapped-up gifts either.

Note: A shortened form of this explanation is included in Narratopia's instructions.

Want to find out more about conversational story sharing? Check out these resources.

- Neal Norrick's book Conversational Narrative: Storytelling in Everyday Talk

- Michael Toolan's book Narrative: A Critical Linguistic Introduction

- Pages 35-45 of my book Working with Stories in Your Community or Organization: Participatory Narrative Inquiry (from which this explanation is drawn)